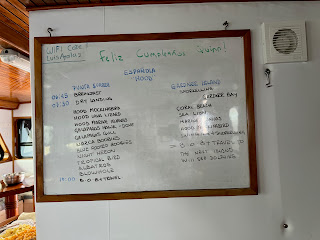

Quinn woke up feeling pretty good on his second day of being a six year old.

In fact, we all did. Since we pulled into our final the marina the night before, there was no overnight travel affecting our slumber. But we did have a quick detour on the agenda that morning. The aptly named Isla Lobos (Sea Lion Island) was just off the coast of the main San Cristobal island. It was a can’t miss stop before we’d fly out later that day. So we motored over for a quick, early-morning hike.

The kids made fast friends, as was becoming their custom that week.

Beyond just sea lions, the island was kind of a “best of” highlights reel to cap off our tour. Of course, blue footed boobies were on the list.

We even got to see a few adolescents and a brand new baby!

Those shell fragments around the mama show how young that baby was. But perhaps the most special encounter was coming upon a juvenile sea lion nursing with its mama.

Aimee, the lactation nurse, predictably lost her mind. [She’s still talking about it as I finally write this post several months after we returned.]

Then it was back on the boat by 7:30 am so we could make our way to the airport. The kids, now thoroughly enamored with the sailor’s life, helped to pull in the dinghies and help load everyone’s suitcases.

And in case there was any doubt about the success of our kids’ charm offensive, even the ship’s chef, Valentino, came out of his tiny galley kitchen to send us off.

That wasn’t the end of the trip for all of us. The crew typically made a full lap of all of the islands in one go before taking some time off. It was a rare group that had the time and cash to complete the entire three week circuit, so the boats picked up and dropped off a portion of their passengers every few days. San Cristobal was one of the main islands, so the boat would normally be picking up a full load of passengers in our place. But Ecuador’s tourism slowdown hit the Galapagos particularly hard. The 20-somethings on the hostel circuit were used to a bit of unrest. But that’s a deal breaker for most cruise passengers. So there wasn’t another batch of people to replace us that day, and the Dutch couple on our trip would have the boat to themselves for the next week.

But a quiet and peaceful sail wasn’t in our immediate future. It was off to the airport for another over-ocean jaunt back to the mainland. The San Cristobal airport was the single-room, one airplane tropical movie set piece that you’d imagine it would be. But that nostalgic charm bit us in that we couldn’t print out our boarding pass. The domestic South American airlines operated like budget carriers in the US in that everything from snacks to luggage was sold a la carte. And that extended to paper boarding passes. When I booked the tickets a month ago from the comfort of my home WiFi and an unassailable cell connection, I couldn’t imagine why I’d need a physical copy of the boarding pass. But when I saw the half-bar of service flicker on and off all morning on a literal desert island, I started to regret my decision. Predictably, I couldn’t get enough service to load the boarding passes, and the ticket agent couldn’t check us in without it. And because the airline agents were working with the same lack of connectivity to the outside world I was, there wasn’t even the option to pay for a boarding pass at the counter.

There were worse places to be trapped, but I was really starting to sweat the predicament I had gotten us into. Mimi had long since developed a sense of when her dad turns into travel-stress dad and immediately picked up that something was off. She was right. So I asked if she wanted to come explore the area around the airport in search of halfway decent cell service or perhaps a cafe with non-robbery coffee prices and customer WiFi. No dice on either. But miraculously Aimee’s phone got a bar just as I was starting to come to terms with us missing our flight. But was her phone and my email password. And I was cursing the biometric security token account protections that make life utterly unlivable if your phone goes offline.

So after pacing out front of the airport talking to myself and angrily tapping our cellphones together in a fashion that would have 100% resulted in an arrest at a US airport, I was able to load my email account from Aimee’s phone and download our boarding passes. Who’s the saint of travel again? Praise him.

The rest of the travel day was pretty easy. Which was a relief, because our layover in Guayaquil was the only time we were in one of the areas of Ecuador rated as a “Do Not Travel” zone by the US Government. That’s where narcoterrorists took over a TV station and held the crew hostage. But the airport wasn’t involved, and I took a calculated risk that a 30 minute layover in a secured airport was a reasonable decision. It was actually the only decision, since there weren’t any flights available from San Cristobal that didn’t go through Guayaquil.

We made it back to Quito without any real dangers beyond running out of snacks. But that is, of course, a real danger to our family. So we went up to the airport cafe before catching a cab to see what they were offering. I was mortified (and deeply offended) to find that meals were starting at $30. I’d be upset about that in the United States. But our kids were on the verge of melting down, and I had to decide how much I value sanity. $4. It turns out that’s how much I value sanity, which was also the price of a yogurt cup. I got one each for the kids, and Aimee and I decided we could last another hour or so into Quito proper.

Still reeling from the airport food prices, I had my taxi skeptometer cranked up to eleven. So I was super defensive when asking the price back into town. The $25 the driver quoted seemed extremely high after paying $0.50 for most cab rides out in the countryside. Aimee audibly guffawed from the back seat, validating my gut feeling about the price. So we shuffled the kids and our luggage right back out onto the curb. From there, I checked the taxi rate board and the current Uber rate. Both were several dollars higher than what the driver was asking. I visibly tucked my tail between my legs and Aimee swore for the first time ever in front of the kids. The shocked expressions from the other three of us brought some much needed levity to the afternoon and reset the hangry weariness that was creeping up in all of us.

I’m nearly always willing and usually even happy to pay a tourist surcharge in places like this. They’re special places with something unique to offer, and often have economies suppressed by external factors way beyond their control. Aimee and I not buying $0.49 bananas probably won’t make much of a dent in that (sorry kids, it’s still a no), but us dropping a few extra bucks for dinner has a real chance of making another family’s life considerably better. So I don’t mind, and I never negotiate over a few bucks in places like this. But after my embarrassment with our first cab, I didn’t even bother to ask the prince in the second. The driver could charge us whatever she wanted when we pulled up to Alicia and Isaias’s apartment. The one was for the people.

I have no idea what the driver was thinking, or if she even noticed my furrowed brow and subconscious lip movements as I was working through all of this as we drove away from the airport. I was already feeling like it wasn’t my finest moment. But when her phone rang and she looked over at me while she talked to the person on the other end, I started to feel particularly self conscious. It didn’t help that she held the phone away from her mouth and asked me in Spanish, “Were you just in another cab?”

“Si.” (Tucks tail even deeper.)

“You know the price into Quito is $25, right?”

“Si.”

“The other driver quoted you $25, right?”

“Si.” (There is no more tail at this point.)

“That was my husband.”

If you’ve ever wondered if a human being could perfectly mirror the facepalm emoji, wonder no more. I did my best to smile in a way that conveyed, “We’re not crazy, it has just been a long day and we’re very hungry.”

I’m not sure I convinced her (or even myself), but at least she didn’t pull over and make us get out of a second cab that day. She got a 100% tip on that trip, accompanied by an apologetic word salad and well wishes to her husband.

🤦🏻♂️

.jpeg)